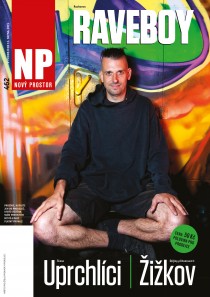

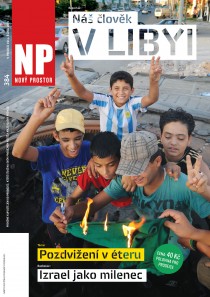

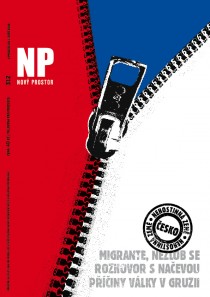

It‘s a forgotten story from World War I, but between 1919 and 1923 some 17,000 Greeks found refuge in several cities in Syria, when Kemal Ataturk‘s army massacred ethnic minorities in Asia minor, while fighting to establish modern Turkey.

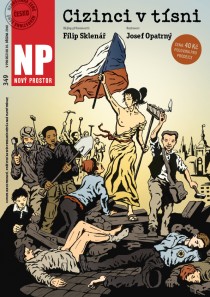

A century later, thousands of Syrian refugees are trying to take the return route travelling through Turkey, only to find themselves drowning in the Mediterranean, jailed for months sometimes in Greek detention centres, or in a legal limbo due to the country‘s strict asylum policy that affects even war refugees.

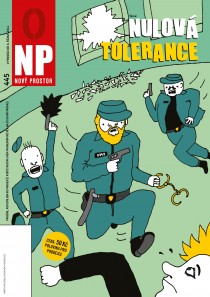

It will not be disclosed publicly, but Greek officials have admitted that a hostile policy would actually send the message to those who are planning to emigrate back home not to take the Greek route. This in essence is the policy dictated by fortress Europe.

It means long bureaucratic and precarious asylum procedures, sometimes accompanied by detention in inappropriate facilities, police ill-treatment that goes uncontrolled and tolerance to the rising xenophobia.

As a result, the Syrian refugees now prefer to move in the shadows before they appear in a friendly European country like Germany or Sweden. The facts are telling: Out of 46,500 Syrians who arrived in Greece, since 2011, only an estimated 1600 have applied for asylum.

A week ago, a ship with 700 refugees from Syria and Iraq was forced to dock at the port of Ierapetra in Crete. The vessel was sailing out of control but to their surprise the coastguards were asked to leave and let the ship reach Italy. Unsurprisingly, 26 unaccompanied children were taken to the detention center where they will stay in terrible conditions, until the police manage to find a solution.

Another group of refugees in Athens decided to take a decisive step in challenging the invisibility and deprivation. One hundred and fifty men, women and even children have camped outside the parliament for more than fifteen days, demanding the right to travel to Europe or the provision of safe conditions for refugees in Greece.

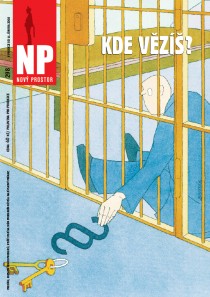

It is one of the very few times where a precarious social group actually demand their legal rights. All of them have heart-breaking stories of loss and pain in the Syrian war, but they also sketch the Greek attitude in dark colours. “They don‘t want us in Greece. But they won‘t let us leave. We are in a place worse than a prison. We can‘t work, we have no housing, no medical care, schools for our kids and we are running out of money,” says Bassel, a 28 year old finance manager.

Indeed some of their compatriots, after surviving the smugglers of the Aegean, are forced to live on the streets, in danger of racist attacks with no medical or other treatment. NGOs, left groups and Greek citizens are providing clothes and food, a common assembly of the Syrian campers of Syntagma and people who express solidarity is established and a campaign runs in social media under the hashtag #syrianrefugeesgr.

The conservative answer on the matter, expressed by the government claims that it cannot do much due to the financial difficulties and European law, which is not on the refugees‘ side but forces the authorities to keep people in Greece. The abstract notion of a “European law” obviously fails to grasp the despair and dead end of the refugees and it fails to understand why they are challenging the status quo.

Soon after the protest gained publicity, authorities found suitable accommodation for the protesters, but it was rejected with dignity and pride on the basis that it constitutes philanthropy and doesn‘t solve the problem. In short: If Greece doesn‘t want to treat victims of war, then they don‘t want to stay in Greece either. Apparently, Athens is seen to be the doorstep of Europe and Greece is trapped in a heartless European policy. Added to that, push back and border surveillance policies are becoming big business now, so one can see the continent investing in fortress Europe instead of actively supporting humanitarian values.

The pressure from below seems to be starting to work. The Syrian protesters have taken their case to the European Court of Human Rights and under the pressure of the UN, 28 Western countries accepted to take 5% of the overall population of Syrian refugees currently living in camps in the neighbouring countries of Syria. Europe needs to do much more than that, as conservative estimations assume that three million Syrians have fled to Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq and another 6.5 million are internally displaced in the country.

In a statement they released online, the Syrian protestors of Syntagma state the obvious: “we escaped death in Syria and we escaped death in the Aegean. We want to live with dignity in Europe. Open up the gates and give us the documents that will allow us to travel there.” Open the gates, fortress Europe.

***

Slovníček:

refugee - uprchlík

fortress - pevnost

smuggler - pašerák