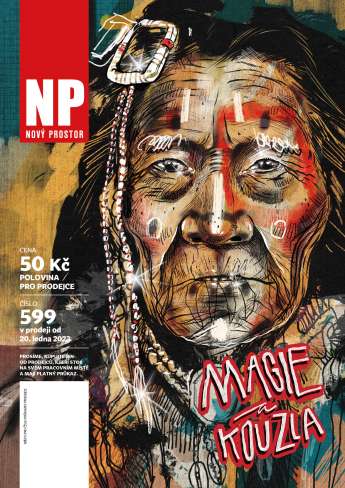

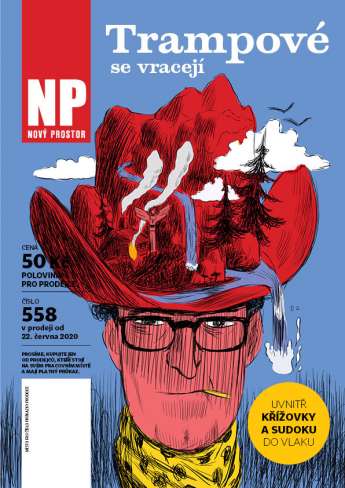

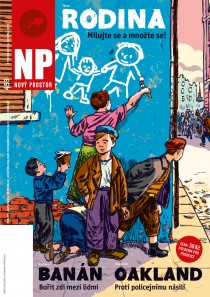

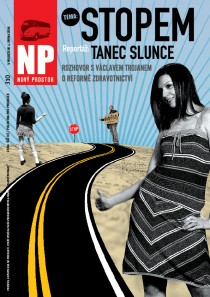

Mentions of Western American culture conjure up images of corrals and Stetson hat-wearing cowboys with belt buckles the size of dinner plates riding broncos and bulls for eight seconds to the wild cheers of fans. You think of wide-open vistas, desert canyons, or mountains stretching as far as the eye can see.

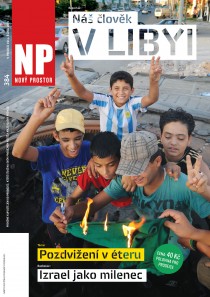

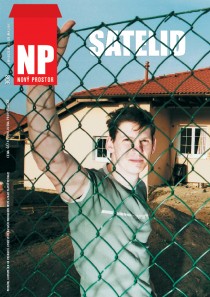

You rarely think of workers from countries like Peru, Chile, Bolivia or even Nepal travelling through vacant, arid wilderness, following vagabond herds of sheep through winter storms or sweltering summer heat. Gaunt, malnourished faces tanned and creased from a life spent outdoors tending animals and fixing fences, hands crisscrossed with scars and swollen knuckles, slight limps and clothing so ragged and torn that in the winter toes peek out from boots and duct tape holds together gloves.

There they are: the modern cowboys, a growing part of the doddering Western economy. They roam the countryside in single occupancy tin shacks on wheels. Men who live and work in near solitude, with only sheepdogs and horses to keep one company, workers brought to the U. S. through the H-2A agricultural visa program to slave away, hidden in the deserts and mountains of the West.

To find this real, contemporary vision of the West, you have to leave the interstates and cities behind, digress from highways to dusty, rarely used roads that cut through the frozen winter sage brush flats where average winter temperatures easily hit below zero and the wind eternally blows, stripping hillsides of dirt and painting the snow-banks brown.

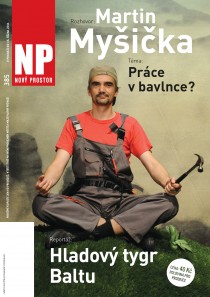

Juan anted up and went off the beaten path as a herder. And now, years later, he’s gone all in with an attempt to expose the underbelly of one of Colorado’s most rugged and abusive industries.

A former sheepherder in Northwest Colorado, Juan tended his own herds for years before he worked his way up to a supply driver position. His knees are blown from his time on the range and a surgery to repair the damage years after the fact, and his face is forever tanned from years exposed to the blistering summer sun and fierce winter winds, yet his infectious smile and good nature has never been stolen.

Juan’s one and only boss during his years on the range, Steve Raftopoulos, of Raftopoulos Ranches, treated Juan so poorly that he unintentionally fed the fire that turned hopeless apathy into a burning desire to fight and change the lives of his fellow ‘borregueros’ Since becoming a naturalized U. S. citizen in 2008, Juan has worked as a self-described labour organizer and advocate for other herders.

He travels the countryside bringing care packages and winter clothing to distant herders. “Because of the injustice I saw and experienced, the bad treatment of workers, the low pay and horrible living conditions is why I got involved and continue to work so hard to help,” Juan said.

Juan was recruited from Chile to be a U. S. sheepherder through the Salt Lake City-based Western Range Association, a company that specializes in the recruitment of foreign workers and the lobbying of Congress on behalf of the American sheep industry. His employer, Steve Raftopoulos, was a former board member of Western Range. Like 75,000 other foreign workers in the United States, Juan signed up for the H-2A visa program in the hope that a 1 to 3 year work contract in the United States would help him and his family get ahead back home. The H-2A visa program is a guest worker program designed to bring agricultural workers into the U.S. for a contractual period of time and then return them to their country of origin. The majority of H-2A workers pick peaches, cotton, grapes or just about any agricultural commodity on the market. Unfortunately for Juan, he joined the ranks of the 2,100 borregueros in the United States, workers who essentially occupy the bottom rung of the pay scales in the H-2A program.

Thomas Acker, a professor of Spanish at Mesa State College in Grand Junction, Colo., and a long-standing social justice activist, has been working with Juan to improve conditions for herders. Together, they say they have observed firsthand some of the countless allegations of abuse from herders, and in response they have started the Promethean battle to improve an industry that flies under most everyone’s radar.

“The way the H-2A visa system works for sheepherders puts too much power in the hands of people who have been proven to abuse the workers,” Acker said.

A recent example they reported on involved meeting a particular sheepherder near Craig, Colo., on the weekend of November 28th and 29th, 2009.

This herder stated that his employer had allowed his H-2A visa to expire, then told the worker that he, as the employer, could do whatever he wants now because the worker was now in the country illegally. The rancher allegedly went further to point out that the worker would be safer staying in the job if he didn’t want to face deportation. Currently Dr. Acker and Juan have turned to legal authorities on his case, with the hope that his visa can be renewed while having him transferred to a new industry within the agricultural community.

Other examples they’ve observed in the field include the confiscation of passports and other important documents by a large majority of ranchers and even the complete control of employee bank accounts, where in some instances workers receive only a handwritten note stating their pay and deductions for the month, instead of being given an actual paycheque or access to a bank. In several cases employers were allowed to not only make deposits, but withdrawals as well. It is expected that full numbers about the abuse of paperwork and paycheque will be released with the final report on the surveys conducted by Colorado Legal Services.

Denver Voice, USA